One bite of the chile verde burrito with papas at Burritos Sarita in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico has the power to shatter any preconceived notions you have about burritos. In it, a soft, smoky flour tortilla wraps a flavorful mix of tender potatoes, caramelized onions, and flame-roasted chile verde, topped with salty and tangy heavy cream.

From beginning to end, the treasure in foil is delicate and neat. Burrito interpretations away from this border town tend to be overstuffed, oversized, overdressed and bloated. But here, the purist burrito, as the locals call it, has only what it needs: one tortilla, one filling.

“It’s our calling card,” Pati Covarrubias, the food truck’s general manager, said of the burrito’s importance to the city. She worked in her aunt Sarita Alfaro’s business from the age of 14.

“My Tia taught me that you have to know how to make every part of a burrito yourself,” she said. Ms. Covarrubias had been up since 3:50 a.m., making the daily hisado, or stew, and kneading the flour tortillas before opening at 8:30 a.m.

On the opposite side of the Rio Grande, this quintessential comida fronteriza—border food—is an integral part of the cultural identity of El Paso, Juarez’s sister city in the United States.

“You can count on someone eating a burrito here every second, every hour of every day,” said Steve Vazquez, owner and burrito maker at La Colonial Tortilla in El Paso. Tortillería sells up to 800 burritos each morning.

No one doubts that Juarez is the birthplace of the burrito, although there are competing origin stories. Some attribute their creation to Juan Mendez, who during the Mexican Revolution sold gusados wrapped in flour tortillas from a donkey-drawn cart called a burrito. Others say they were born by workers who took these wraps on the go and then called them burritos because they resembled the rolled up blankets that sat on donkeys in the fields. Some say they were named after the children who helped women carry their shopping — cutely nicknamed burritos — and paid with these wrappers.

Both cities strive to uphold and preserve purist burrito traditions while defining the ultimate burrito experience. However, it is hard to deny that there is a friendly but deep rivalry.

Mr. Vasquez said La Colonial has crowds of customers from Juarez who cross the border mainly for its burrito de chile relleno with chile con queso. And Ms. Covarrubias said she has regulars from El Paso who seek out her burrito de chile verde con daddies.

“I’ve always been afraid to try a burrito from another place because it’s not the same,” People brought us some from Juarez, and they are good, but not like ours.”

Ms. Covarrubias once caught her daughters bringing home burritos from El Paso. “You can imagine how I scolded them!” she said, laughing.

As competitive as they are, both cities can agree that the same basic elements make for a burrito worth bragging about: it must be made from a flour tortilla with an emphasis on one filling, no complimentary toppings, and eaten on the go.

Here’s more on three important things:

Freshly prepared flour cake

It’s no coincidence that one of El Paso’s most popular burerrias is also a tortilla factory. At La Colonial, burritos are rolled to order with hot tortillas straight from the press machine. “My grandparents started making tortillas by hand,” Mr. Vasquez said, “but they couldn’t keep up with the demand, so after a few years they installed a machine.”

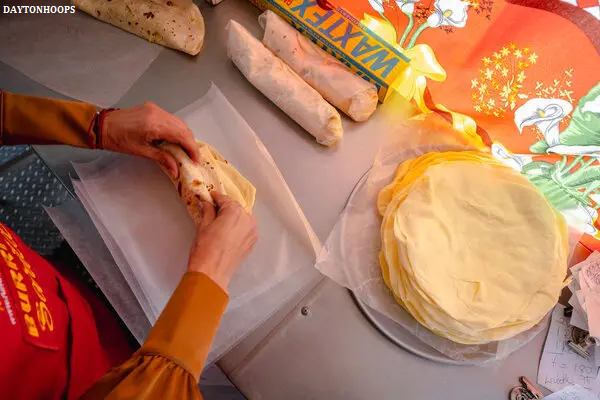

At Burritos Sarita, they deny to change their artisanal procedure. Every morning, the fresh masa, or dough, is kneaded and rolled out by hand with a palote, a heavy rolling pin, and cooked on a hot griddle in the back of an open truck.

The dough constituents are the same on both sides of the border flour, swabs, water, incinerating greasepaint, and fat. The water should be “as hot as your body can handle so the mass doesn’t harden,” Ms. Covarrubias said. The leavening agent ensures that the cakes rise with a smooth texture. Without it, cakes can have a folded structure; but too much and they become as hard as crackers, she said.

Finally, you need fat. In the region, lard, vegetable fat and butter are the most popular options. Ms. Covarrubias and Mr. Vasquez choose lard, although vegetable oil works great for truly meatless burritos.

Customers know good flour tortillas, Ms. Covarrubias said. “ They feel the difference so well that indeed other Juárez burrería possessors come to us. I won’t reveal them, but they don’t mind standing in line for a burrito that’s en su punto,” she said. That is, to the point.

A filling that can stand on its own — and without fillings

Purist burritos tend to have one unusual topping, perhaps with added cheese or maximum avocado. The key difference between El Paso and Juárez is that north of the border you’ll find evidence of American influence with ingredients like chili con queso, brisket or sausage mixed with eggs instead of macaque or chorizo.

Still, these elements translate into home-style stuffing that’s strong in its own right. The brisket at La Colonial is prepared from scratch almost like a guizado. Their chile con queso is served spooned over a traditionally made chile relleno or boldly seasoned refried beans. Chicharrón en salsa, Picadillo, Frijoles con Queso, Chile relleno, Chile Verde con Papas, Chile Verde and Chile Colorado are all classics on both sides of the border.

Put your thumb and middle finger together in a circle—that’s how thin purist burritos should be. If there is salsa, it is added to the guizado or topping, not served on top.

Packed and eaten on the go

Simplicity is crucial: no clutter, no clothes, no fuss and no dishes. Purist burritos are light, neat and extremely convenient.

“I offered the electricians and plumbers if I could make a plate for them and add more stuff,” Mr. Vazquez said. ” But they say they love eating them on the way to work and how easy and accessible they are.” Oscar Herrera, a cook who splits his time between the two cities, said the region is a key market for aluminum foil companies because of the popularity of on-the-go burritos.

Ms. Covarrubias worries about the upcoming burrito she wakes up so early to make. Her grown children have said they’d like to work at a burrito truck, “but they don’t want to put in the time to properly learn hisado or make the flour tortillas you find in stores now,” she said.

Maybe she will find hope across the river. Mr Vazquez’s 11-year-old daughter, Mia, said she wanted to continue her father’s cause. ” We will see,” he told with a buzz.

On both sides of the Rio Grande, the love and dedication to the craft of making what they consider authentic burritos is perhaps what defines the style the most. Mr Vasquez said that creating them “has to come from the heart”.

Ms. Covarrubias echoed that sentiment. “The main ingredient is mucho amor.”